Part I - When to use full infinitives, bare infinitives, or gerunds

An Iran-based English teacher asked me by e-mail sometime in 2019 how to answer this multiple-choice test question: “Peter, you have been working so hard this year. I am sure you must be tired. My suggestion for you is (take, to take, taking) some time off.”

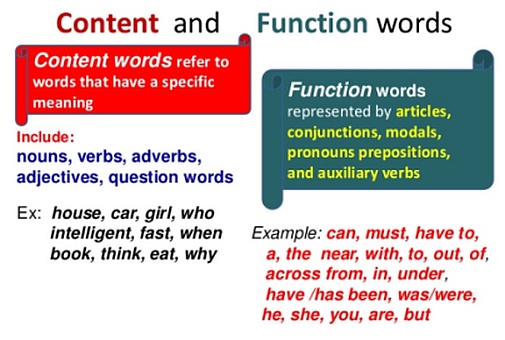

IMAGE CREDIT: CALLANSCHOOL.INFO

The three answer choices she provided are the bare or zero infinitive “take,” the full infinitive “to take,” and the gerund “taking.” I thus replied to Ms. Farhad H. that with a fair knowledge of these grammar forms and based on how the third sentence sounds, the correct answer is the full infinitive “to take”: “My suggestion for you is to take some time off.”

The much tougher question though is why the answer should be “to take” and not “take” or “taking.” To answer it correctly, we need to review the infinitives and gerunds as verbals, which are words that combine the characteristics of a verb and a noun.

IMAGE CREDIT: ENGLISHSTUDYPAGE.COM

Recall that a full infinitive has the form “to + base form of the verb,” as in the full infinitive “to rest” in the sentence “The tired watchman decided to rest,”; where “to rest” is the direct object (the receiver of the action) of the operative verb “decided.”

IMAGE CREDIT: 7ESL.COM

On the other hand, a bare or zero infinitive is an infinitive that, to work properly (or at the very least smoothly), needs to drop the function word “to” and use only the verb’s base form, as in “rest” in “We saw the watchman rest for a while.” In this sentence, the bare infinitive “rest” is the direct object of the verb “saw.” (Using the full infinitive “to rest” here sounds awkward and iffy, “We saw the watchman to rest for a while ” so it's obviously couldn't be a corect answer).

As to a gerund, recall that it’s a form of the verb that ends in “-ing” to become a noun, as in the gerund “resting” in “Resting recharged the watchman for the rest of his shift.” In that sentence, the gerund “resting” is the subject, a role that its full infinitive equivalent—although also a noun form—plays very awkwardly in this particular instance: “To rest recharged the watchman for the rest of his shift.”

IMAGE CREDIT: SLIDESHARE.COM

This grammar complication in choosing the correct verbal brings us to the four general ground rules for using an infinitive or gerund in particular sentence constructions:

1. Use the infinitive as subject to denote potential, as in “To forgive is a good thing.” On the other hand, use the gerund to denote actuality or fact, as in “Forgiving made her feel better.”

2. Use the full infinitive as a complement or object to denote future ideas and plans, as in “His life-goal is to teach.” On the other hand, use the gerund when denoting acts done or ended, as in “She chose teaching.”

3. Use the full infinitive as a complement for single action, as in “He took a leave to travel,” and likewise for repeated action, as in “Evenings we come here to rest.” On the other hand, use the gerund for ongoing action, as in “The fashion model finds resting necessary after every shoot.”

4. Use the full infinitive as object for a request, as in “He asked me to wait,” for instruction, as in “She instructed me to rehearse,” and causation, as in “He was forced to resign.” On the other hand, use the gerund for attitude, as in “She thinks teaching is a noble profession,” and for unplanned action, as in “She found jogging to her liking.”

On top of these ground rules, we must firmly keep in mind that the primary basis for choosing an infinitive or gerund is the specific operative verb of the sentence. We also need to recognize that some operative verbs can take full or bare infinitives, others can take gerunds, and the rest can take both.

In Part II, we’ll focus on the choice between full infinitives and bare infinitives. (June 27, 2019)

Part II - When to use full infinitives, bare infinitives, or gerunds

In Part I, to answer a question from an Iran-based English teacher, I started laying out the basis for why the full infinitive “to take” is the correct answer in this multiple-choice statement: “Peter, you have been working so hard this year. I am sure you must be tired. My suggestion for you is (take, to take, taking) some time off.”

After a quick review of full infinitives, bare (zero) infinitives, and gerunds—they are the so-called verbals, or words that combine the characteristics of verb and noun—I presented four general rules for choosing between infinitives and gerunds for particular sentence constructions. This time I’ll focus on the choice between full infinitives and bare infinitives when used as subject, object, or complement of a sentence.

There are really no hard-and-fast rules for choosing the full infinitive or the bare infinitive. While the primary determinant for the choice is the operative verb and syntax of the sentence, we’ll only find out which of the two infinitive forms works—or at least works better—by first using the full infinitive as default. When it doesn’t work, simply use the bare infinitive.

(LEFT IMAGE): ENGLISHSTUDYPAGE.COM (RIGHT IMAGE) PINTEREST.COM

CHOOSING BETWEEN THE FULL INFINITIVE AND THE BARE OR ZERO INFINITIVE

The full infinitive is, of course, the only choice when it’s the subject of the sentence, as in “To give up isn’t an option at this time.” The bare infinitive form won’t work as it reduces the full infinitive to a verb phrase: “Give up isn’t an option at this time.” (Take note tthough that the gerund form, “giving up,” works just fine for that sentence: “Giving up iisn’t an option at this time.”)

Now let’s look at particular grammatical and syntax situations when using the bare infinitive becomes a must:

1. Use a bare infinitive or bare infinitive phrase when it’s preceded by the adverbs “rather,” “better,” and “had better” or by the prepositions “except,” “but,” “save” (in the sense of “except”), and “than.”

Examples: “She would rather stay single than marry that obnoxious suitor.” “With her deceitful ways, you had better reject her overtures to team up with you.” “They did everything except beg.”

The two sentences become faulty-sounding when the full infinitive is used: “She would rather to stay single than to marry that obnoxious suitor.” “With her deceitful ways, you had better to reject her overtures to team up with you.” “They did everything except to beg.”)

2. The verb auxiliaries “shall,” “should,” “will,” “would,” “may,” “might,” “can,” “could,” and “must” should always be followed by a bare infinitive: “I shall fire those scalawags.” “We might visit next week.” “You must investigate right away.” (Faulty with the full infinitive: “I shall to fire those scalawags.” “We might to visit next week.” “You must to investigate right away.”)

3. The object complement should be a bare infinitive when the operative verb followed by an object is a perception verb such as “see,” “feel,” “hear,” or “watch”: “She watched him do the job and saw him do it well.” “We heard him castigate an erring general.” (Faulty with the full infinitive: “She watched him to do the job and saw him to do it well.” “We heard him to castigate an erring general.”)

4. The object complement should be a bare infinitive when the operative verb is the helping verb “make” or “let”: “She always makes me feel loved.” (Faulty with the full infinitive: “She always makes me to feel loved.”) However, the helping verb “help” itself can take either a full infinitive or a bare infinitive as object complement. Formal-sounding with the full infinitive: “She helped them to mount the rebellion.” Relaxed, informal-sounding with the bare infinitive: “She helped them mount the rebellion.”

Again, as a rule, use the full infinitive as default to see if the sentence will work properly and sound right. Otherwise, use the bare infinitive.

This two-part essay appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in the Campus Press section of the June 27, 2019 print edition of The Manila Times, © 2019 by the Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.