The great importance of parallel

construction in presenting ideas

By Jose A. Carillo

Part IV – Presenting ideas in parallel

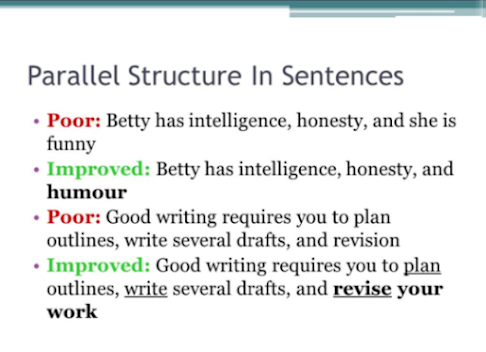

We saw in the first three parts of this essay that the consistent use of parallel structures is the key to more readable, more forceful, and more polished sentences. We also learned that for clearer and more cohesive sentences, we should always use parallel structures when presenting various elements in a list, when comparing elements, when joining elements with a linking verb or a verb or being, and when joining elements with correlative conjunctions.

IMAGE CREDIT: TEACHERSPAYTEACHERS.COM

Before winding up our discussions on parallel construction, we will take up two more techniques for harnessing parallelism to give structural balance and better rhythm to our sentences. We will discover that these techniques can dramatically improve our writing and give it a distinctive sense of style.

Use parallel structure for adjectives and adverbs. We should also aim for parallel patterns when using adjectives and adverbs in our sentences, seeking structural balance for them in much the same way as we do for noun forms, verb forms, infinitives, and gerunds.

Unparallel construction: “She danced gracefully, with confidence and as if exerting no effort at all.”

Here, we have a stilted sentence because the modifiers of the verb “danced” have taken different grammatical forms: “gracefully” (adverb), “with confidence” (adjective introduced by a preposition), and “as if exerting no effort at all” (adverbial phrase).

Parallel construction: “She danced gracefully, confidently, effortlessly.” The consistent adverb/adverb/adverb pattern gives the sentence a strong sense of unity and drama.

Unparallel construction: “The gang attempted an audacious bank robbery that was marked by lightning speed and done in a commando manner.” The sentence reads badly because the three modifiers of “bank robbery” are grammatically different: “audacious” (adjective), “marked by lightning speed” (participial phrase), and “done in a commando manner” (another participial phrase).

Parallel construction: “The gang attempted an audacious, lightning-swift, commando-type bank robbery.” The sentence reads much more forcefully because of its consistent adjective-adjective-adjective pattern for all of the modifiers of “bank robbery.”

Use parallel structure for several elements serving as complements of a sentence. For more cohesive and forceful sentences, we should always look for a suitable common pattern for their complements. Recall that a complement is an added word or expression that completes the predicate of a sentence. For instance, in the sentence “They included Albert in their soccer lineup,” the phrase “in their soccer lineup” is the complement.

Unparallel construction: “We basked in the kindness of our gracious hosts, walking leisurely in the benign morning sunshine, and the palm trees would rustle pleasantly when we napped in the lazy afternoons.” Here, we have a confusing construction because the three elements serving as complements don’t have a common grammatical pattern: “the kindness of our hosts” (noun phrase), “walking leisurely in the benign morning sunshine” (progressive verb form), and “the palm trees would rustle pleasantly when we napped in the lazy afternoons” (clause).

Parallel construction: “We basked in the kindness of our gracious hosts, in the benign sunshine during our early morning walks, and in the pleasant rustle of the palm trees when we napped in the lazy afternoons.” The sentence reads much, much better this time because the three complements are now all noun phrases in parallel—“in the kindness of our gracious hosts,” “in the benign morning sunshine during our early morning walks,” and “in the pleasant rustle of the palm trees when we napped in the lazy afternoons.” Note that all three have been made to work as adverbial phrase modifiers of the verb “basked.”

In actual writing, of course, the need to use parallel structures in our sentences will not always be apparent at first. As we develop our compositions, however, we should always look for opportunities for parallel construction, choose the most suitable grammatical pattern for them, then pursue that pattern consistently. Together with good grammar, this is actually the great secret to good writing that many of us have been looking for all along.

Part V – Presenting ideas in parallel

Pursuing Parallelism Beyond the Sentence Level

In the earlier parts of this series, we reviewed the various ways of achieving parallelism when constructing sentences. We saw how using the same function words can match and balance the clauses and phrases in a compound sentence, and how presenting our ideas in parallel not only emphasizes that they are equally important but also clarifies the point that we are making about them. This time, we will see how parallelism can be pursued beyond the sentence level to make our writing clearer and more forceful, and our language more elegant and pleasing to the ears.

We must not wrongly assume, of course, that we should aim for parallelism only for such elaborate pieces as expository writing or speeches. We need parallel structures even for such mundane requirements as tables of contents and résumé listings. In the sample table of contents below, for instance, note the meticulous parallelism in the consistent use of noun phrases for the headings in the first level, gerunds for the headings in the second, and simple nouns in the third.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Our Uses and Misuses of English [noun phrase]

A. Mastering the Parts of Speech [gerund phrase]

1. Nouns [noun]

2. Pronouns [noun]

3. Verbs [noun]

4. Adjectives [noun]

5. Adverbs [noun]

6. Prepositions [noun]

7. Conjunctions [noun]

8. Determiners [noun]

B. Grappling with the Language [gerund phrase]

1. Academese [noun]

2. Legalese [noun]

3. Gobbledygook [noun]

4. Clichés [noun]

II. Our Grasp of English Usage and Style [noun phrase]

A. Constructing Sentences [gerund phrase]

1.Structure [noun]

2. Logic [noun]

B. Acquiring Style [gerund phrase]

1. Form [noun]

2. Technique [noun]

III. Our Familiarity with the English Idioms [noun phrase]

When a table of contents is organized along such parallel lines, readers can follow the logic and flow of our ideas much more easily—even if those ideas aren’t expressed in complete sentences.

Now, let’s see how parallel structures can likewise make our résumés clearer and more persuasive. Below, under “Work Experience,” note that the titles for skills are consistently stated as gerunds, and those for work descriptions as verb phrases:

WORK EXPERIENCE

1. Writing and Editing: [gerunds]

• Produced news and feature stories for the company magazine [verb phrase]

• Researched and drafted speeches for the CEO [verb phrase; not, say, “Researching and drafting speeches for the CEO,” which are gerund phrases]

• Developed scripts for special occasions and organized events [verb phrase; not, say, “Scripts for special company occasions and organized events,” which is a noun phrase]

2. Coordinating Events: [gerund]

• Acted as company spokesman for the mass media [verb phrase, consistent with the first item under “Writing and Editing”]

• Represented the company in major public forums [verb phrase; not, say, “Company

representative in major forums,” which is a noun phrase]

Parallelism as a tool for achieving clarity and for evoking feeling in exposition

Given its effectiveness in focusing ideas and in giving symmetry to language, it also shouldn’t be surprising that parallelism is a very powerful tool for achieving clarity and for evoking feeling in expository prose. Feel the elegant sweep and quiet tug of emotion in this passage from “The Night Country” by the American literary naturalist Loren Eiseley:

“In some of us a child—lost, strayed off the beaten path—goes wandering to the end of time while we, in another garb, grow up, marry or seduce, have children, hold jobs, or sit in movies, and refuse to answer our mail. Or, by contrast, we haunt our mailboxes, impelled by some strange anticipation of a message that will never come."

Even more consummate in pursuing parallelism was the English historian Edward Gibbon. Take a look at this superb passage from his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

“There are two very natural propensities [that] we may distinguish in the most virtuous and liberal dispositions, the love of pleasure and the love of action. If the former is refined by art and learning, improved by the charms of social intercourse, and corrected by a just regard to economy, to health, and to reputation, it is productive of the greatest part of the happiness of private life. The love of action is a principle of a much stronger and more doubtful nature. It often leads to anger, to ambition, and to revenge; but when it is guided by the sense of propriety and benevolence, it becomes the parent of every virtue, and, if those virtues are accompanied with equal abilities, a family, a state, or an empire may be indebted for their safety and prosperity to the undaunted courage of a single man. To the love of pleasure we may therefore ascribe most of the agreeable, to the love of action we may attribute most of the useful and respectable, qualifications. The character in which both the one and the other should be united and harmonized would seem to constitute the most perfect idea of human nature.”

Having seen the many wonders that parallelism can do, we now have every reason to pursue it more vigorously in our own writing.

[END OF SERIES ON PARALLELISM]