BASIC AND ADVANCED

PARAGRAPH TRANSITION TECHNIQUES

By this time many of us should already be familiar with the English paragraph and could whip up one or several of them with great ease. The general concept for the paragraph that we normally follow is, of course, that it’s a collection of sentences that all relate to one main idea or topic and that have unity, coherence, and adequate development. This particularly applies to the typical expository paragraph, which starts with a topic sentence or controlling idea that the exposition then explains, develops, or supports with evidence.

As we all know, however, not all paragraphs need a topic sentence; some paragraphs could simply be indicators of breathing or structural pauses in narratives, dialogues, and explanatory statements that are marked for the purpose by a new, usually indented line (digital word processing, of course, now provides a stylistic device to even get rid of indentions, as in this very exposition that you’re reading now). Either way, paragraphs no doubt serve as functional transitions from one set of thoughts to another, and this is where many people—whether beginning writers or professionals who just want to set their thoughts down clearly and logically—get confused as to precisely how transitions between paragraphs should be done.

In “Making Effective Paragraph Transitions,” a four-part series that I wrote for my English-usage column in The Manila Times in early 2006, I extensively discussed the various techniques that a writer can use to effectively bridge a succeeding paragraph to the one preceding it—a process that I explained works in much the same way as logically bridging adjoining sentences in an exposition. In this week’s blogspot, I am presenting in retrospect all four parts of that series for the benefit of new Forum members and those who missed reading it the first time around. I hope that the discussions will help them gain much greater competence and confidence in the paragraphing craft. (November 9, 2013)

MAKING EFFECTIVE

PARAGRAPH TRANSITIONS

Part I – Basic forms of paragraph transitions

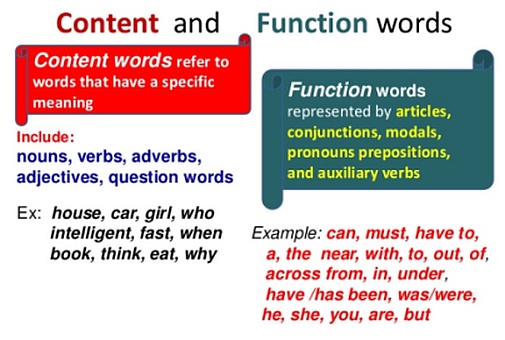

Contrary to what some people think, making effective paragraph transitions is really not that difficult. This is because most of the familiar devices we use for linking sentences can serve as transitional devices for paragraphs as well. For instance, such linking words as “besides,” “similarly,” “above all,” and “as a consequence” can effectively bridge a succeeding paragraph to the one preceding it in much the same way that they can bridge adjoining sentences. It’s true that some experienced writers make it part of their craft to minimize the use of these highly visible paragraph “hooks,” but to the beginning writer, they are indispensable for interlocking paragraphs into logical, cohesive, and meaningful compositions.

IMAGE CREDIT: PINTEREST.COM

IMAGE CREDIT: PINTEREST.COM

Highly visible paragraph transition “hooks” for beginning writers

Choosing a paragraph transition is largely determined by which of the following major development tasks the new paragraph is intended to do: (1) amplify a point or add to it, (2) establish a causal relationship, (3) establish a temporal relationship, (4) present an example, (5) make an analogy, (6) provide an alternative, or (7) to concede a point. Once a choice is made, it becomes a simple matter to find a suitable paragraph transition from the very large body of conjunctive adverbs and transitional phrases in the English language.

Before discussing the major types of task-oriented paragraph transitions, however, let us put things in better perspective by first looking into two of the most basic forms of paragraph transitions. One way is to simply repeat in the first sentence of a succeeding paragraph the same operative word used in the last sentence of its preceding paragraph, as the word “process” does in this excerpt from William Zinsser’s On Writing Well:

“Ideally the relationship between a writer and an editor should be one of negotiation and trust…The process (underscoring mine), in short, is one in which the writer and the editor proceed through the manuscript together, finding for every problem the solution that best serves the finished article.

“It’s a process (underscoring mine) that can be done just as well over the phone as in person…”

The other basic paragraph transition form is substituting a synonym or similar words for the chosen operative word. For instance, in the passage above, we can use the similar phrase “this kind of review” instead to begin the second paragraph: “This kind of review can be done just as well over the phone as in person…” This transition may not necessarily be better than the first one, but it has the advantage of giving more variety to the prose.

Now we are ready to discuss the task-oriented paragraph transitions.

Amplifying a point or adding to it. If we need to elaborate on an idea at some length, we can effect the transition to a succeeding paragraph by using whichever of the following transitional words and phrases is appropriate: “also,” “moreover,” “furthermore,” “in addition,” “similarly,” “another reason,” and “likewise.”

Establishing a causal relationship. When we want to discuss the result of something described in a preceding paragraph, we can achieve a logical transition by introducing the succeeding paragraph with any of the following transitional words or phrases: “so,” “as a result,” “therefore,” “consequently,” “then,” and “thus.”

Establishing a temporal relationship. This is the easiest paragraph transition to make. We can make the desired chronological order by simply using the following adverbs or adverbial phrases to introduce the succeeding paragraph: “as soon as,” “before,” “afterward,” “after,” “since,” “recently,” “eventually,” “subsequently,” “at the same time,” “next,” “then,” “until,” “last,” “later,” “earlier,” and “thereafter.”

Presenting an example. For this purpose, we can achieve a quick transition by using the following words or phrases to begin the succeeding paragraph: “for instance,” “for example,” “in particular,” “particularly,” “specifically,” and “to illustrate.”

Making an analogy. By using such words as “also,” “likewise,” “similarly,” “in the same manner,” and “analogously,” we can make an effective transition to a succeeding paragraph that intends to make a comparison with what has been taken up in a preceding paragraph.

Providing an alternative. When alternatives to an idea presented in a preceding paragraph need to be discussed, we can introduce them in a succeeding paragraph by using the following transitional words: “however,” “in contrast,” “although,” “though,” “nevertheless,” “but,” “still,” “yet,” “alternatively,” and “on the other hand.”

Conceding a point. An effective strategy to demolish a contrary view is to quickly concede it in a paragraph introduced by such transitional words as “to be sure,” “no doubt,” “granted that,” “although,” and “it is true.” The rest of the paragraph can then present arguments to discredit the wisdom of that contrary view.

For more complex compositions such as essays and dissertations, however, we will usually need more sophisticated paragraph transitions than the conjunctive adverbs and transitional phrases we have already taken up above. We will discuss them in detail in Part II of this essay.

Part II – Extrinsic and intrinsic paragraph transitions

Because of its nuts-and-bolts approach to the subject, Part I of this essay must have given the impression that making paragraph transitions is simply a mechanical procedure, a matter of just tacking on a familiar conjunctive adverb or transitional phrase between adjoining paragraphs. This, as we shall soon see, is not the case at all. It just so happens that conjunctive adverbs and transitional phrases are the best starting point for discussing the subject, for they have a built-in and overt logic in them that can apply to a very wide range of situations. As we progress to the more complex types of compositions, however, we will need much less obtrusive and more elegant ways of bridging paragraphs into cohesive and meaningful compositions.

There are two general categories of transitions for bridging paragraphs: extrinsic or explicit transitions, and intrinsic or implicit transitions.

Extrinsic or explicit transitions. They primarily rely on such familiar introductory words as “however,” “therefore,” and “moreover” to show how an idea that will follow is related to the one preceding it. The various conjunctive adverbs and transitional phrases that we already took up in the previous essay belong to this category.

Transitions of this type are very handy and give paragraphs very strong logical interlocks, but when overused, as in legal documents that employ long strings of “whereases,” “provided thats,” “therefores,” and “henceforths” to drive home a point, their prefabricated logic can become very distracting, annoying, and unsightly. This is why it is advisable to minimize their use in formal compositions. For academic essays and dissertations, in particular, the usual suggested limit is no more than one extrinsic transition for every paragraph and no more than three for every page.

Intrinsic or implicit transitions. This category of transitions, on the other hand, makes use of the natural progression or “flow” of the ideas themselves to link paragraphs logically. Instead of using the usual conjunctive adverbs or transitional phrases, they effect paragraph transitions through a semantic play on key words or ideas in the body of the exposition itself. A sentence that performs an intrinsic paragraph transition usually:

(1) repeats a key word or phrase used in the preceding paragraph and makes it the takeoff point for the succeeding paragraph, or else

(2) uses a synonym or words similar to that key word or phrase to do the transitional job. Part I of this essay already gave examples of this type of paragraph transition.

At this point, we will now complete the picture by adding the pronouns “this,” “that,” “these,” “those,” and “it” to the list of basic implicit transitional devices, for these pronouns can often bridge adjoining paragraphs as effectively while minimizing the distracting overuse of the same nouns in the composition.

To better understand how intrinsic paragraph transitions work, let’s assume that we have already written the following first paragraph for an essay:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.”

Now how do we make an intrinsic transition to the next paragraph of this essay?

The task, of course, basically involves constructing an introductory sentence for that next paragraph. We will now look into the various intrinsic transition strategies for doing this, from the simplest to the more complex ones.

Strategy 1: Use a summary word for an operative idea used in the last sentence of the preceding paragraph.

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“The idea was at first totally out of the question to me. I was such in a hurry to get back to Manila because of an important prior engagement…”

Strategy 2: Use the pronoun “this” for an operative idea in the last sentence of the preceding paragraph.

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“This was actually not a very easy decision to make. I had to be in Manila later that week for a business meeting…”

Strategy 3: Use the pronoun “that” for an operative idea in the last sentence of the preceding paragraph.

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“That proved to be the most memorable part of our tour. Despite my misgivings…”

Strategy 4: Use a more emphatic transition by using “that” to intensify an operative word or idea used in the preceding paragraph.

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“That decision had very serious and far-reaching consequences for me. I missed an important meeting in Manila and lost a major account…”

Part III – “It,” “such,” and “there” as paragraph transitions

We have already looked into several extrinsic or implicit strategies for making a transition to a new paragraph from the one preceding it. All of these strategies begin the new paragraph with a sentence that either repeats a key word or phrase used in the preceding paragraph, or else substitutes a summary word or pronoun such as “this” or “that” for that key word or phrase. This time we will look into the use of the words “it,” “such,” and “there” as devices for similarly making such paragraph transitions.

To illustrate how these words work as transitional devices, we will use the same prototype first paragraph that we used in the previous column, as follows:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.”

Strategy 5: Use the anticipatory pronoun “it,” otherwise known as the expletive “it,” to begin the new paragraph. We know, of course, that many teachers of writing frown on this usage, claiming that it seriously robs sentences of their vigor. As the two examples below will show, however, this device can be very efficient as a paragraph transition:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“It was past midnight at our Boracay cottage when my friend suddenly sprung the Palawan idea on me…”

or:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“It was farthest from my mind that my friend would even think of a Palawan trip just when we were ready to fly to Manila…”

It’s true, however, that too many expletives in a composition can be very distracting, so we must use this paragraph transition device very sparingly.

Strategy 6: Use the pronoun “such” in the first sentence of the new paragraph to echo an operative idea in the preceding paragraph.

”As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

”Such was what happened to my best-laid plans after my friend chanced upon a Palawan tour brochure…”

We must take note, though, that some grammarians find this use of “such” as a noun semantically objectionable. They would rather use “such” as an adjective or adverb to make such transitions:

”As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

”Such a radical departure from our travel plans was very unpalatable, but my friend was so headstrong about it…”

or:

”As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

”Such was my consternation about the Palawan idea that I actually considered going back to Manila without my friend…”

Strategy 7: Use the pronoun “there” in the first sentence of the new paragraph to introduce the new idea that will be developed. See how effective this transitional device can be in effecting shifts in time, place, scene, or subject:

”As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

”There was a time when I would summarily reject unplanned trips like that…”

or:

”As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

”There was a very compelling reason why I didn’t want to make that Palawan trip, but my friend would hear nothing of it…”

For the same reasons that they shun the expletive “it,” however, many teachers of writing strongly caution against this usage, arguing that it encourages lazy writing. Thus, as a rule for short compositions, more than one paragraph beginning with “there” would probably be too much.

We will now go to another type of paragraph transition, one that exhibits both extrinsic and intrinsic properties. The most common transitional devices of this type are the prepositional phrases used to begin the first sentence of paragraphs that set off events by order of occurrence, or to indicate changes in position, location, or point of view. Typically, these prepositional phrases are introduced by a preposition, but unlike such usual stock transitional words or phrases as “before,” “after,” and “as a result,” they carry specific information about the subject being discussed.

Some examples:

Prepositional phrases serving as paragraph transitions marking the sequence of events: “At 8:00 in the morning…”, “By noon…”, “At 6:00 in the evening…”

Prepositional phrases serving as paragraph transitions marking changes in position: “At sea level…”, “Below sea level…”, “Above sea level…”

Prepositional phrases serving as paragraph transitions marking changes in location: “In Manila…”, “In Rome…”, “In London…”

Prepositional phrases serving as paragraph transitions marking changes of point of view in the same composition: “As a private citizen…”, “As a professional…”, “As a public official…”

To conclude our discussions on paragraph transitions, we will take up in Part IV the so-called “deep-hook” paragraph transitions—the type that blends so effortlessly and so unobtrusively with the developing prose that we hardly notice that the transition is there at all.

Part IV – Deep-hook paragraph transitions

We will now discuss “deep-hook” paragraph transitions—the type that subtly works out its bridging logic by making itself an intrinsic part of the idea being developed. Unlike the usual conjunctive adverbs and transitional phrases such as “but,” “however,” and “as a result,” deep-hook paragraph transitions don’t call attention to themselves. They do their job so unobtrusively that readers hardly notice they are there at all.

To show what they are and how they work, we will use the same prototype first paragraph that we used to illustrate the other types of paragraph transitions:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.”

Strategy 8: Use the last word or phrase of the preceding paragraph as the first word or phrase of the next paragraph, then make it the takeoff point for developing another idea. This is the simplest of the deep-hook paragraph transitions and is most effective when limited to two or three words, such as “unplanned trip to Palawan” in this example:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“An unplanned trip to Palawan was farthest from my mind at the time because I was so in a hurry to get back to Manila...”

When it uses too many words, this type of paragraph transition may still work but it tends to be repetitive and clunky.

Strategy 9: Use an earlier word or phrase in the last sentence of the preceding paragraph as the first word or phrase of the next paragraph, then make it the takeoff point for developing another idea.

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“Our tour guide had apparently spared no effort in foisting the outrageous idea on my friend’s impressionable mind...”

Strategy 10: As the next paragraph’s takeoff point for developing another idea, use a word or phrase in a sentence other than the last sentence of the preceding paragraph. To establish its logic, however, this type of paragraph transition usually needs a multiple hook—perhaps two or more operative words or phrases from the preceding paragraph:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longe friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and to the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“That my friend should specifically insist on Palawan after already visiting several vacation resorts in the Visayas was terribly upsetting to me...”

Here, the multiple hooks are “friend,” “several vacation resorts,” and “Visayas” from the second sentence of our prototype first paragraph, and “Palawan” from its last sentence.

Strategy 11: Use an “idea hook,” one that distills into a single phrase an idea expressed in the preceding paragraph, then use it as takeoff point for developing the next paragraph. This is the subtlest and most sophisticated form of paragraph transition of all, and its skillful use in compositions often indicates how good a writer has become in the writing craft.

Here are two idea hooks for a paragraph that will follow our prototype first paragraph:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“Giving in to my friend’s utterly capricious idea upset all of my well-laid plans for the remainder of that month...”

or:

“As a traveler, I am a stickler for schedules and will adamantly resist any change in my itinerary, no matter how attractive that change might be. This was my cardinal rule until I accompanied a longtime friend from Paris on a five-day visit to several vacation resorts in Luzon and the Visayas, and for which Boracay Island was to be our final stop. At the last minute, however, on her insistence and egged on by our tour guide, I reluctantly broke my own rule and agreed to join her on an unplanned trip to Palawan.

“That spur-of-the-moment decision led to an experience so delightful that I vowed never again to so doggedly take the well-beaten path in my travels...”

In practice, however, deep-hook paragraph transitions should not be used to the total exclusion of the conventional conjunctive adverbs and transitional phrases. In fact, compositions that use a wide variety of paragraph transitions flow better and are generally more readable than those that use only one type.

This ends the four-part retrospective on “Making Effective Paragraph Transitions.” I hope that the discussion has clarified whatever lingering doubts you might have had about how to properly bridge paragraphs in your expositions.

**********

This four-part exposition first appeared in the column “English Plain and Simple” by Jose A. Carillo in four weekly installments from September-October 2013 in the Internet edition of The Manila Times,©2013 by the Manila Times Publishing Corp. All rights reserved.